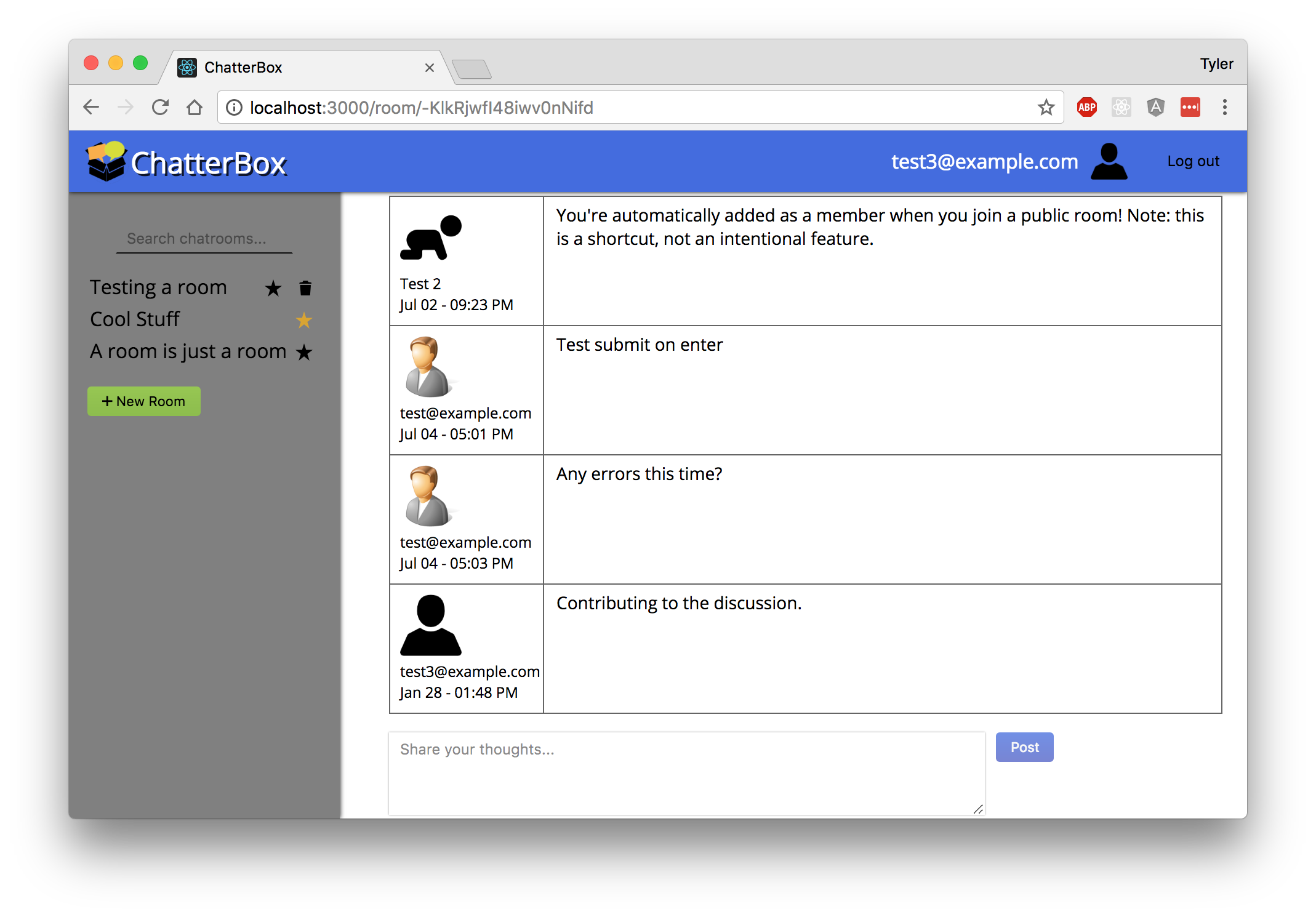

ChatterBox — originally titled BlocChat — was a project designed to add an element of complexity to architectures and technologies that I am already familiar with. The big difference between it and previous Angular projects was that ChatterBox uses a JavaScript based back-end – Firebase – provided by Google. This was a fantastic motivating factor, because, with a database, the site didn’t simply have to look and feel dynamic, it could actually serve up and save off content. Firebase made it very easy to create something that just works!

Firebase

The Firebase API provides access to a JSON-type database. It’s a fairly simple tool for organizing datasets, but its really the API framework, two- and three-way data binding, and feature set that makes it so powerful.

The first few steps to building a chat application involved simply slapping something simple together, but soon I had to think more carefully about how to organize the database. Firebase documentation recommends having a ‘flat’ structure, which, in my mind, corresponded to some of the relational databases that I’ve worked with in the past. It focused on using Ids to connect related types of information, rather than storing and managing duplicate info or having a very deeply nested structure that wasn’t conducive to relating data together.

Here is an example of what not to do:

{

"rooms":{

"$room_id": {

/* room properties */

"messages": {

"$message_id":{ /* message properties */ }

}

}

}

}

The above structure is not optimum for fetching subsets of information. For example, if all you want to do is list the rooms that are available, this structure would force you to unnecessarily download all the messages along with the room info.

Here is the recommended ‘flat’ approach (a simplified version of what I actually did):

{

"rooms":{

"$room_id": { /* room properties */ }

},

"messages": {

"$room_id": {

"$message_id": { /* message properties */ }

}

}

}

With this method, you can quickly and cleanly request a list of rooms and then only list the messages for a specific room when the user chooses to. Now, to a certain extend, this does create some duplication as you store IDs to reference other ‘tables’ in the database. You would even have to create additional tables if you wanted to simulate a relational database’s many-to-many relationship. Despite the potential for duplication, the ‘flat’ structure is likely more performant and can facilitate creating Firebase rules, which is another topic I researched quite a bit.

Bloc’s curriculum didn’t quite adhere to Firebase’s documentation, so I decided to go a bit off the beaten path to align with best practices and accomplish a more secure data organization. This allowed me to do a bit more with Firebase and my app, and I even provided some feedback that I hope will improve Bloc’s curriculum for this project (as far as Firebase data structures go). I kept my data structure as ‘flat’ as possible, but my ambitions for ChatterBox led to some pretty complex data sets as I tried to keep track of public vs private chatrooms, room membership and invitations, and private user data (like favorite chatrooms) as well as public user data (user info for attributing posts, or searching for friends).

Angular Services

The ‘flat’ data approach led to many complications as I began to write services that were intended to facilitate the application flow and provide relevant info at the appropriate time. While AngularFire makes interacting with Firebase very simple, I was attempting to build services that would only perform the minimal number of transactions possible with the back-end. This meant that it was important to store traceable references to all the results of database queries and, when available, return them rather than querying again. While this sounds fairly straight-forward, the data wasn’t always structured or query-able in ways that facilitated this approach. For example, using the ‘flat database structure and creating fine-tuned access rules (a topic which I’ll explore further below) meant that I often had to store related pieces of information in different locations and artificially aggregate it for referencing later.

The services I created were also intended to play a specific role, but the needs of the app, as well as the organization of the data, caused overlap that didn’t always sit well with me. For example, the UserService, whose primary role was authentication had to keep user data accurate in multiple locations (I know, not very DRY). One of those other locations was a data table that aggregated all users’ basic info (so that, as a user, I could look other users up as well as see who posted in various chatrooms as an intelligible name rather than an alphanumeric id string). I had created a separate service for that specific function called UserDataService, but when a user updates his/her own information, the UserService has to talk to the UserDataService to get and set that data. Even inside of the UserDataService the data had to be retrieved and updated from/in different places in the database.

That same kind of cross-service communication and disparate data storage locations is not uncommon in ChatterBox and it struck me that interdependence among services may not be the best design. On the other hand, and as I’ll explain, the only way I could see to create relatively secure data was to save it in different locations, so that particular challenge probably didn’t have a solution without moving away from Firebase as the security layer for the database.

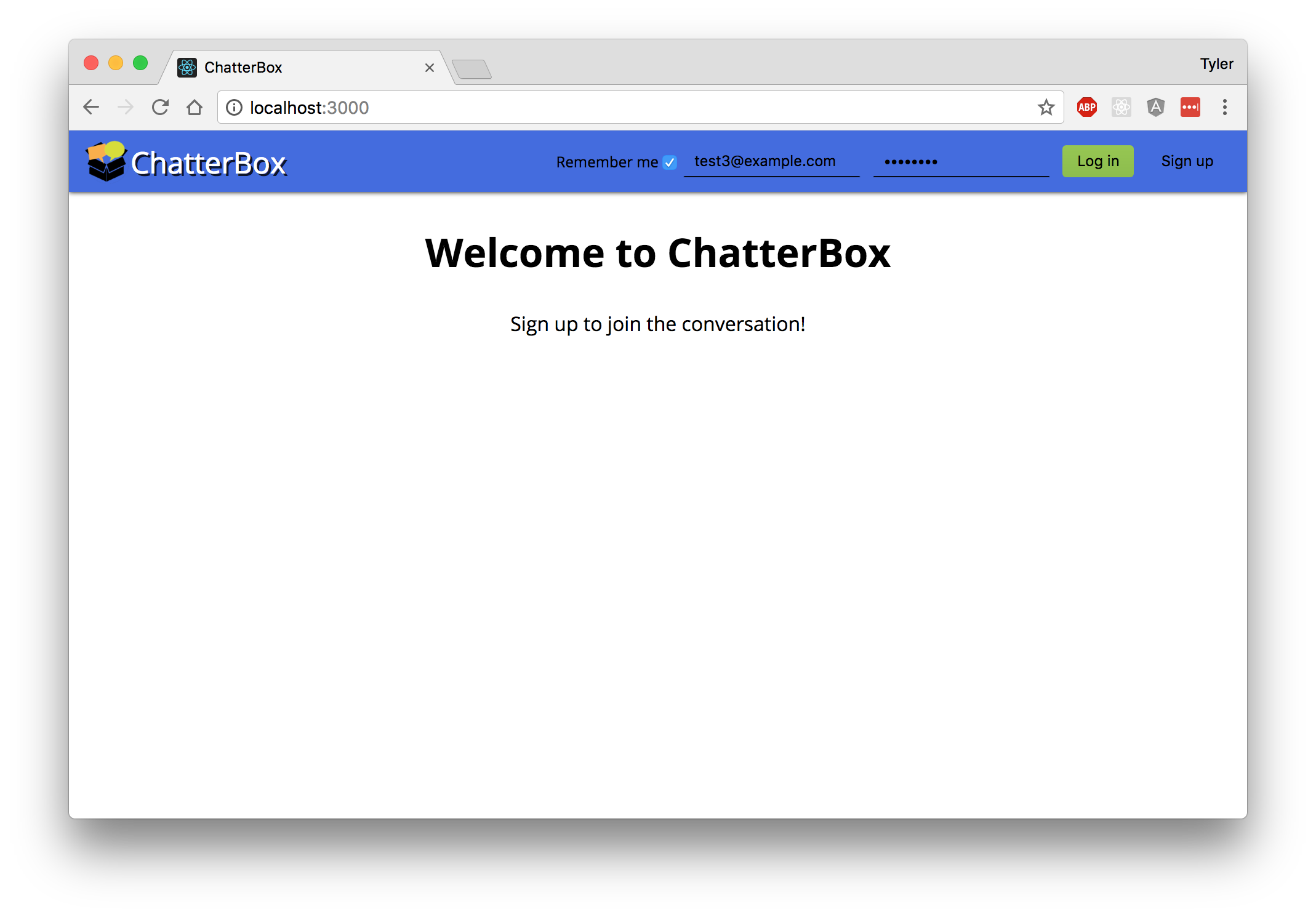

User Authentication

Very early on in the project, my vision for ChatterBox was one where users could not only identify themselves, but log in and have a personalized experience that also allowed for privacy. One of the user stories I was considering right off the bat was one in which users could send each other messages that only they could see (direct/personal messaging). A similar use case is easily imagined with group conversations that you wish to remain closed to the public and accessible by invitees only. While there are many considerations and design choices that went into addressing those user stories, the central one was user authentication. Luckily, Firebase provides a fantastic structure and API to facilitate this. All I had to do was build my UserService to expose the important aspects of that API. However, that certainly didn’t solve all of the design challenges surrounding user authentication.

Once I had a UserService, I had to figure out how to use it to lock down the site when a user wasn’t logged in, or was logged in as someone who shouldn’t be able to see certain content. Each page had to respond to the user authentication state appropriately and guide people intuitively to sign up and log in without those pieces becoming intrusive. My primary strategy to accomplish this behavior was to inject the UserService into all the application controllers. Since the UserService was the mechanism for logging in, it was a reliable place to get the current login status. I could then use ngif, ngshow, or nghide to control the visibility of relevant UI messages. I also injected all Firebase-related services into the UserService so that their cached data could be wiped when the user logged off, both protecting potentially sensitive information and preventing authorization errors in the Firebase data. With more time, I would gladly explore this area in more depth as I’m sure there are more effective ways of achieving this even more reliably.

Security

Firebase provides ‘rules’ as a means by which to lock-down different data segments. Given my desire to provide the ability to have ‘private’ conversations on ChatterBox, I felt it was crucial to establish a corresponding ruleset. This was quite a struggle and required a lot of research, iterative testing, and several not-inconsequential data re-structuring efforts. For a while I was worried that my vision wasn’t possible with the JSON model of Firebase and the way they implemented rules, but I discovered that it was simply impractical.

To summarize a lot of investigation, Firebase rules are established from the ‘top’ of the hierarchy down and the search for access stops as soon as one is reached. This means that you cannot have multiple access rules within a tree. There’s “one rule to rule them all” - so to speak.

To demonstrate, here is a simplified data structure:

{

"users": {

".read":"auth != null",

"$user_id": {

".write": "$user_id === auth.uid"

}

},

"rooms": {

".write": "auth != null",

"$room_id": {

".read": "root.child('invitations/'+auth.uid+'/'+$room_id).exists()"

}

},

"messages": {

"$room_id": {

".read": "root.child('invitations/'+auth.uid+'/'+$room_id).exists()",

".write": "root.child('invitations/'+auth.uid+'/'+$room_id).exists()"

}

},

"invitations": {

"$user_id": {

".read": "auth.uid === $user_id",

"$room_id": {

".write": "auth != null"

}

}

}

}

As you can see, there are both .read and .write permissions that can be associated with the data in Firebase. All access is based on the authenticated user, which means we must take the approach of preventing undesirable access first, and then consider possibilities for adjusting structure or access to accommodate user stories. First let’s consider our security considerations:

- Users must be invited to a chatroom to find it.

- Users must be invited to a chatroom to view its messages.

- Users must be invited to a chatroom to create messages in it.

- Users must not be able to edit information about other users.

- Users must not be able to see which rooms other people are members of.

With those things in mind, let’s enumerate the user stories we need to accomplish:

- Users must be able to create chatrooms.

- Users must be able to create messages.

- Users must be able to update their own information.

- Users must be able to read other users’ information.

Using these guides, we can identify the required .read and .write permissions to complete each user story and security constraint. Let’s look at the users part first. auth != null is used to prevent unauthenticated users from performing an action. Since we want users to be able to read all user data, we set .read at the top level.

{

"users": {

".read":"auth != null",

"$user_id": {

".write": "$user_id === auth.uid"

}

}

}

This will apply to any information at that level and below. It’s important to not that it cannot be overwritten by another .read at a lower level. The most general permission that applies to a user will ‘win’ if more specific ones are also given. Each users’ information is stored as a value corresponding to a key of the user’s ID. In the rules, we use a variable to represent that key so that we can leverage the user’s ID in the rule specification. We only want to allow the user to .write data to this location if they are authenticated with the same ID as the key. This will prevent users from editing other peoples’ information.

Let’s take a look at a more complicated user story sequence. Any authenticated user can create a chatroom. We allow this by giving .write permissions at the top level of rooms. Now, creating a room doesn’t allow someone to read the contents of that room because we only allow .read if the currently authenticated user has the room ID listed in the invitations/$user_id location.

{

"rooms": {

".write": "auth != null",

"$room_id": {

".read": "root.child('invitations/'+auth.uid+'/'+$room_id).exists()"

}

}

}

Luckily, when a user creates a room, they have access to the ID of the resulting room entry. We use this ID to create a key in invitations/$user_id using the same ID.

{

"invitations": {

"$user_id": {

".read": "auth.uid === $user_id",

"$room_id": {

".write": "auth != null"

}

}

}

}

Now the .read test that looks for invitations/'+auth.uid+'/'+$room_id will pass for the user, allowing him/her to read the details of the room. But, what about the messages for a chatroom?

{

"messages": {

"$room_id": {

".read": "root.child('invitations/'+auth.uid+'/'+$room_id).exists()",

".write": "root.child('invitations/'+auth.uid+'/'+$room_id).exists()"

}

}

}

Notice that in the messages area, no access is given to the the top level, this means that a user can only access the messages for a room if they know the room ID and, as we have seen, they only can only read the room ID if they have been invited to the room. So, as an invitee to a room, I have the ID and can access messages/$room_id at which point, I have .read and .write access to the messages for that room. To bring things full circle, each message for a room has a user ID listed as the ‘author’. When displaying a message, we don’t show the user ID in the GUI, that’s not very user friendly. Instead, we query the users area for an entry matching that ID and get that user’s picture and display name to put on the page. This request to the users area is made as the authenticated user, which is allowed by our read permission.

As you can see, setting up these rules can get very tricky when you want to limit access based on things like ‘author’, ‘invitee’, whether or not a chatroom is ‘public’ or ‘private’, or whether or not someone has ‘subscribed’ to a chatroom. One shortcoming of my current model is that every invitee technically has permissions to edit any post in the chatroom. Of course, my front-end makes that difficult to accomplish, but I don’t doubt that a determined hacker could accomplish some mischief. To solve this, we would have to create another area where messages were associated with user IDs and read access was given to anyone who knew the message ID, but write access was given only to the person whose user ID matched the author’s ID.

Furthermore, all of these access complications are really just feeble attempts to emulate a relational database with permissions enforced at the back-end. But, Firebase’s JSON based data structure doesn’t lend itself to the same kinds of data references.

Boxing it all up

Writing ChatterBox was a very interesting challenge. I found it to be a very instructive way to practice creating angular Services and Directives to accomplish the modularity and functionality that I desired. However, it seems to me that the particular nature of Firebase was a bit more of a distraction than Bloc probably intended. It would have been very easy to set up a chat application without thinking of security or of minimizing server calls, but it seems to me that those are both problems that a developer should be thinking about. Yet a developer often has so many things to think about, they must be given priorities. There’s something to be said for building a product that works and then refining it later. That’s probably the biggest thing that I learned: If I were to do this project again, I would focus on building an application that accomplished the user stories first and then moved on to optimizing and trimming fat where it seemed most beneficial.